|

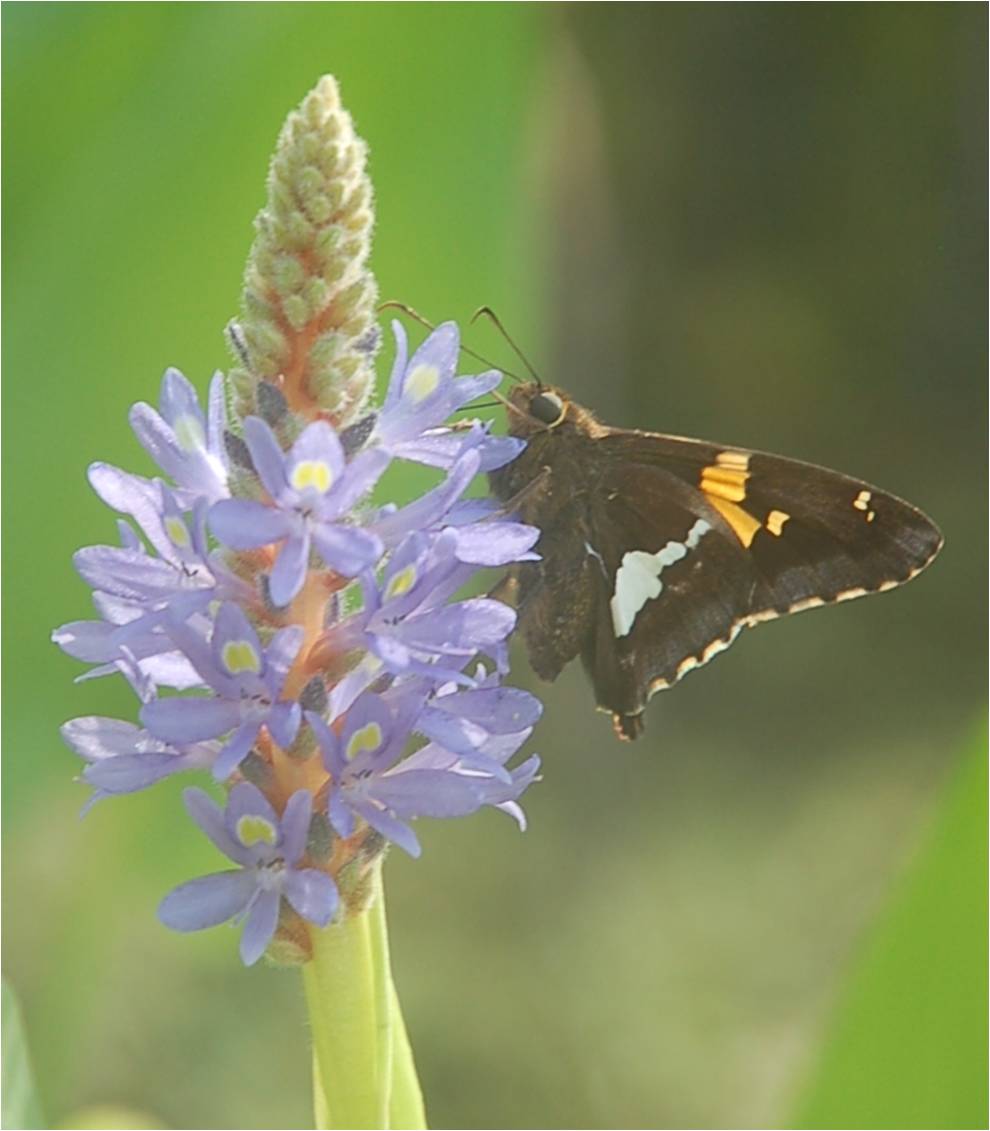

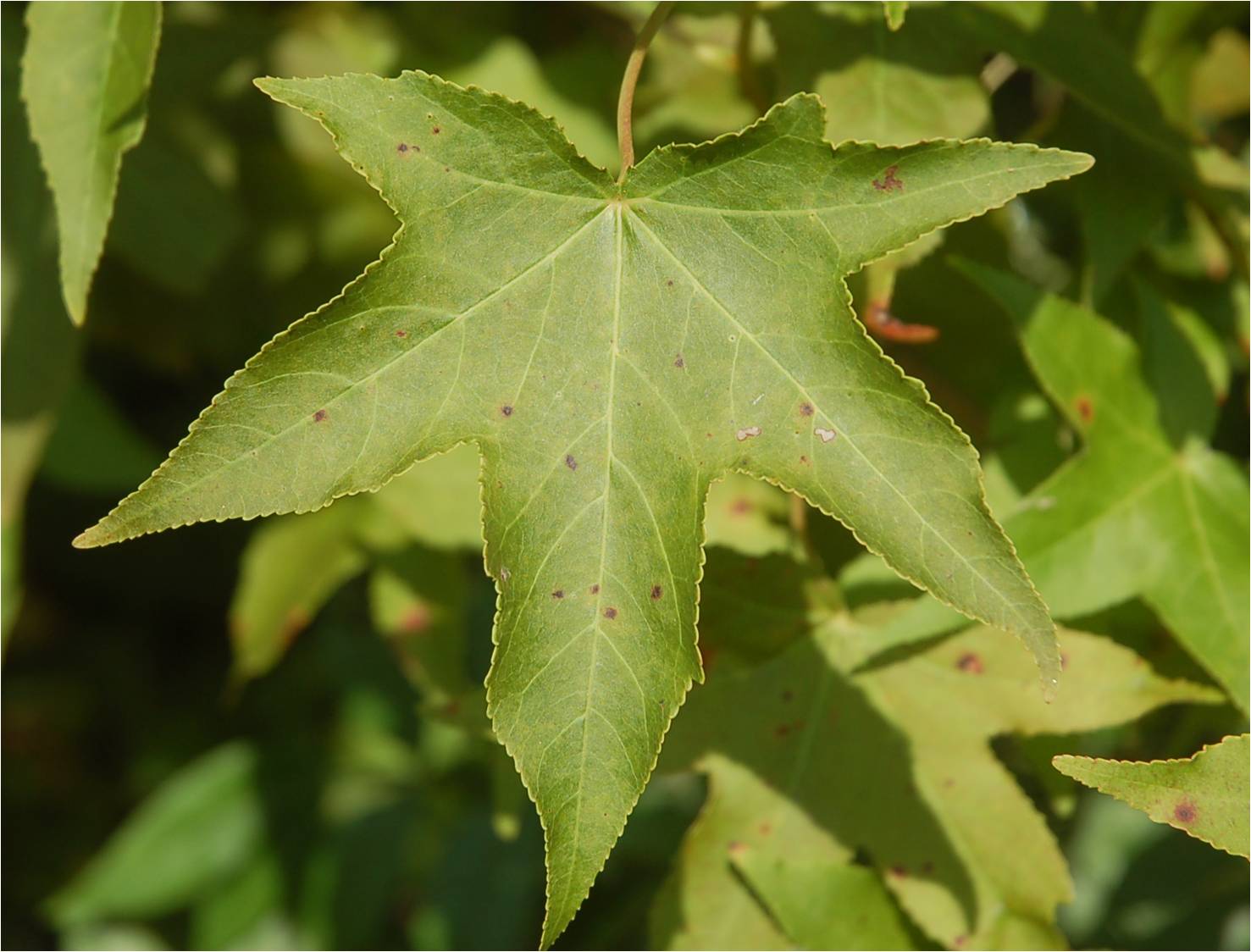

Diary of an Urban Watershed, Week 3by Tracy S. FeldmanBlog post week 3 (14 July 2014): Seeing the trees for the forestAt Glennstone Preserve this past Sunday, I walked past the gazebo, over the lawn, and passed through the wall of green leaves into the forest. It’s easy to see all of that greenery, the whole forest, as something monolithic—like one large coordinated living thing. There are good reasons why we might see a forest in this way. Forests breathe, and ecologists can measure the flow of oxygen and carbon dioxide as they exhale and inhale over time. In last week’s blog post , I discuss the network of mycorrhizae linking tree roots in the soil. Some trees are connected even more directly through root grafts, which can be good or bad for trees, depending upon whether nutrients or diseases are passed from tree to tree. So in many ways, the forest can be viewed as one living thing. Yet the forest is made up of myriad different living things. Even among just the trees of the forest, there are many different types of trees, and often many individuals of each type. At Glennstone Preserve, I have documented at least 54 species of shrubs and trees, and probably many more tree species occur there. As part of the environmental education activity for this past week, we searched the leaf litter to find leaves of different tree types, and tried to figure out how many species were in our sample. We also used our sense of touch to distinguish among individual trees. The cool part of that exercise is that we can distinguish an individual tree from others if we make careful enough observations—just like each person is unique, so is each tree. Yet we know we are all people. How hard can it be to distinguish one type of living thing from another, if we can distinguish individuals from each other? Very. Nature does not make it easy for us to figure out what counts as different “types”. “Species” is often defined as a group of genetically similar organisms that can interbreed. Yet we often distinguish among species by characteristics we can see. If variation among individuals of each of two species is great enough that the characteristics of the two species overlap, they might seem to be one very variable species. Indeed, sometimes what scientists thought was one species have turned out to be many, when they examine genetics or even differences between species at different life stages. For example, what scientists thought was one species of tropical butterfly turned out to be ten species. On the other hand, sometimes the species boundaries are blurred such that living things we categorize as different species may still interbreed. For example, closely related oak species sometimes mate with each other, producing successful hybrids. Bacteria and some fungi often give us few or no visual characteristics to go on, so we have to figure out what species are by their genes. This is tricky, as we often have no idea who can mate with whom—no way to use our tried and true definition of a species. As if all of that weren’t hard enough, symbioses (when different living things live together) make it even more difficult to figure out what a species is. Lichens, for example, are a partnership between algae and fungi, and many of the partners are not found in nature by themselves. Algae are not at all closely related to fungi, but the combination of an alga and a fungus can function as a species.

Perhaps given these difficulties, it isn’t hard to see why we often don’t know how many species (of living things, or even just trees) are in a forest. We have no idea how many species are in our world. Yet we are discovering new ones all the time. Biologists make these discoveries not just in distant rainforests and inaccessible mountain ranges but in our own backyards. Botanists (plant biologists) have discovered 10 new plant species in North Carolina since the year 2000. Even humans, the most studied species on the planet, are ripe for discoveries of new species. Large numbers of species (bacteria, mites, etc.) live on us and in us, and these living things influence our health (for good and for ill), and even perhaps our moods. We don’t even have a good handle on the biodiversity of our own symbiotic partners, let alone those of all of the other living things on Earth. Also, it is difficult to get a handle on biodiversity because we need to know where and how to look for living things. Even if people know how to find new species, they have to look at the right time to find them. Organisms come and go. When I was at Glennstone Preserve on the 28th of June, mushrooms of many fungal species were out after recent rains. The above-ground parts of these fungi were all gone by the following week (one mushroom was eaten within an hour after I photographed it). Birds migrate through Glennstone in the spring and fall. Even if they do not live here for long, these species depend upon forest patches like Glennstone for food and shelter along the way. Even some plants can remain dormant for a while, so they may be undetectable for years, right under our noses. Why is it important to know how many, or which, living things are around us? Can’t we just lose ourselves in the green mass of a forest? Certainly we depend on other organisms, even if we aren’t always sure how or why, and we are learning about new dependencies all the time. It’s hard to assess the health of a forest (or anyplace) without knowing more about the species there. And there are many threats to the health of our forests. I may address that more next week. I always find it comforting when I find high biodiversity in a place. It’s almost relief that these other organisms still exist, even as humans are causing extinctions of other ones. For me, knowing something about which organisms live in a place also makes me feel more connected with that place. A forest has stories to tell, and knowing what’s in a forest can open a window to those stories. Selected References:

Links: |

Natural history photos by Tracy S. Feldman.

Created and maintained by

tsf

Last updated July 2014

Created May 2014